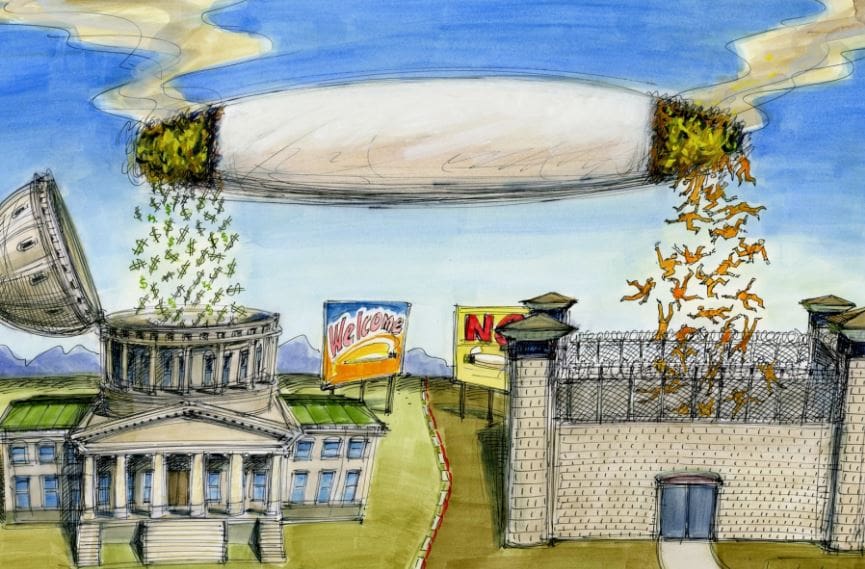

Legalization of cannabis, for medication or for pleasure vs. Benefit of public interest

A renewed debate over laws banning or allowing the use and supply of cannabis worldwide has been fueled by the legalization of the supply and use of cannabis for “recreational and medical” purposes in several US states, Europe[1] and other countries since 2012. Proposals for drug legalization have raised concerns they could lead to increased cannabis use and related harm, and questions about how cannabis for non-medical purposes can be regulated to alleviate these concerns.

In the European Union (EU)[2], a limited distribution system has evolved in the Netherlands since the 1970s, and this has seen further developments in recent years. The advantages and disadvantages of these regulated systems are being closely observed. Likewise, in Germany[3], the new government plans to legalize cannabis. The draft cannabis control law includes the licensed cultivation of soft drugs and their sale in specialty stores for persons over 18 years of age.

The ‘cannabis social club’ model has been increasingly mentioned in drug policy debates.

While quite a number of EU countries support cannabis legalization (according to a new study)[4], it turns out that the Netherlands surprisingly has the most pessimistic views on cannabis legalization, with only 47% of respondents supporting legalization. This is the lowest level among the eight European countries surveyed, despite its famous cannabis sales cafes.

The tax revenues on soft drugs certainly depends on the tax rate and the tax structure. Soft drugs have a small volume and a high value. In this respect, they are comparable to tobacco. In fact, soft drugs are much more expensive per gram than tobacco.

If we rely on the analysis of the benefit from the case of cannabis use in Dutch or German coffee shops (cafés), as a general rule, income tax is also paid on profits realized from illegal activities. Therefore, although selling cannabis in cafés is illegal (but tolerable and obvious), cafes pay profit tax on their earnings, as well as payroll tax and social security for their employees. The administration of cafés is often imperfect, mainly because there is no administration of supplies. In these cases, the profit is estimated on the basis of information obtained from indirect sources. The profit of a coffee shop in many cases is taxed at a ceiling rate of 52%. This is the highest group of personal income tax, which starts with a relatively moderate taxable income of around € 57,500. There are two segments / groups in the income tax of firms. In the first group (profit up to € 200,000), the tax rate is 20%. Higher earnings are taxed at a ceiling rate of 25%. The net profits of distributed firms are taxed at the progressive rate of personal income tax. The turnover of the cafés is estimated at 600 million euros (7% of GDP), although this is a conservative estimate[5].

Coffee shops do not pay value added tax (VAT) on the sale of cannabis. This is due to the fact that VAT is a harmonized tax in the EU. Under EU rules, no value added tax is levied on illegal activities. Legalizing cannabis sales in the Netherlands would not automatically make cannabis taxable for VAT.

The preliminary conclusion may be that the potential total budgetary effects of imposing an indirect tax on the consumption of soft drugs are done in combination with the regulation of the production and supply of soft drugs. Based on a maximum tax rate of up to 100%, which is moderate compared to the tax rate on cigarettes, these effects on the state budget can be estimated at approximately 1 billion Euros per year, although it is calculated for countries like the Netherlands, where there is an early regulation and market with tradition in the EU.

Other countries have for years been analyzing not only the taxation model, but also other effects to be considered for citizens and their economies.

Whereas, the news thrown for decision-making in Albania, after a National Questionnaire according to the format of the staff of Prime Minister Rama should be analyzed with local specifics regarding the rule of law situation (Albania is in the last place for law enforcement in the Balkans)[6], both internally, but also externally, where formalization and fiscal and economic administration is far from the European average, but also Balkan.

The legalization of this narcotics meanwhile, after over former 8 years of government priority, where the achievements of the government “Rama 1” in this approach received the “blessing” of Pope Francis does not seem so legitimate in the perception of Albanian citizens.

Thus, the idea of legalizing cannabis initially for medical use, if it is not intended by socialist party ideologs to divert attention from price increases of nearly 9 months, as well as the liquidity needs of a budget that has been languishing for years, it needs to enter in the calendar of a real public consultation (not with questionnaires), or of a referendum on the decision-making process of future that will have to build the infrastructure of the activity, the cost-benefit analysis, as well as the social, economic and moral impacts, to be clarified with exhaustive answers, which not yet known even as concept note.

This process first needs to answer some basic questions such as:

– Is this government initiative another way of managing to save electricity?

– Will the cultivation process of cannabis affect water reform and screaming problems with misuse of tasks not performed by the local government?

– How will the sector strategies, the governing political program and the budget bills be updated?

Without wanting to list many other questions, we can make some empirical approaches regarding the current perception of this initiative, which is considered the same as the heated discussions regarding the opening of brothels in Albania.

First, we, the citizens, experts and civils society need to be acquainted with the dimensions that cannabis cultivation will take within the agricultural sector, for the sake of the necessary analysis to know how much it can affect the current activities in the agricultural sector, how could be the impact in the balance of the labor market and the chain of the value of the agricultural market together with the accompanying policies for social and economic services.

Who and on what basis of education will be the specialists of this agricultural crop?

What about the current inventories, which are subject to criminalization according to the Criminal Code, will be used and how will they be registered in the fiscal books and the fiscalization process?

In fact, when the analysis extends to the national level, this new strategic policy for agriculture and medicine, means that the whole of Albania will treat the administration of the process, as part of the local economy. Civil society will have to change all studies based on the impact of this drug on Albanian families, school textbooks, as well as the re-planning of local budgets and the state budget, as a subculture of agriculture with a special fiscal regime.

Secondly, the impact on the growth of agricultural exports, in the conditions of a fast legal process in time will directly affect the distortion of sector policies and will spread the image in the international market, that Albania has already legalized everything mentioned as negative policy in the reports of The State Department, the European Commission and other monitoring organizations, as a country, which is already the originator of cultivation and exportation of soft drugs, where cannabis is the job that Albanians know how to do best. Meanwhile, this new activity will have to influence of the government behavior to modify its entire governing program, for the sake of influencing and shifting from actually policy an important part of agriculture economy and labor force, where the profit is easier and without much competition. On the other hand, this policy deviation will further increase the structuring and perfection of corruption and money laundering, in which a significant group of Albanian citizens have years of experience.

Third, it is a moment that brings back to the attention of fiscal policy, analyzing what tax model should be adapted to be implemented so as not to affect other activities as well as the principles of taxation on tax justice, equity in implementation and fair taxation. In this approach we, the voice of expertise and the voice of civil society will have to get to know each other, (a) to understand the analysis about who will benefit directly and indirectly, (b) to advocate the public interest and know the budget interest, as well as (c) other policies that will conditionate the budget expenditures stemming from the adoption of a new soft drug legalization policy.

Fourth, the possibility for informal and criminal money to have a momentum to enter into the legal economy through fiscal amnesty initiative, declared by Prime Minister Rama, as a legal process in parallel with the legalization of cannabis. In reality this recycling of dirty money policy, together with the fiscal amnesty initiative will likely create a strong social and moral shock, which is superfluous to the disoriented social integrity of the still unemancipated society compared to the emancipated societies of EU countries.

Fifth, informal money in a market where money laundering influences government policies and strategies creates new premises for manipulating free voting, through the orientation of easy money and in higher amounts than usual by directly serving the electoral interest. of its proponents and to the detriment of a fair and equal electoral process for the parties.

Sixth, this policy launch gives hope to criminal elements / groups that political time is working for them by killing hope for the rule of law, as it will be perceived as a negative example of the political process towards the unwillingness to build a future of based on knowledge values and competitive market for youth.

In this context, we should emphasize that almost all Eastern European countries doesn’t have taken cannabis legalization initiatives.

In closing, cannabis advocates argue that the decision not to prosecute individuals for cannabis use in some countries may also apply to registered groups of individuals, in order to allow a closed system of cannabis production and distribution.

Currently, the model is rejected by national authorities in Europe.

[1] https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/cannabis-policy/html_en

[2] https://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/c0703c01-0d38-11e7-8a35-01aa75ed71a1.0001.03/DOC_1

[3] https://europeanlawblog.eu/2022/01/11/cannabis-legalization-in-germany-the-final-blow-to-european-drug-prohibition/

[4] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-07/european-support-for-cannabis-legalization-grows-study-shows

[5] https://revistaicdt.icdt.co/wp-content/Revista%2074/PUB_ICDT_ART_VANDENEN%20DE%20L.%20J.%20M._Tributacion%20de%20las%20drogas%20La%20experiencia%20holandesa_Revista%20ICDT%2074_Bogota_16.pd

[6] https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/global

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.