From the devaluation of the euro to a National Export Strategy, 2026 – 2036

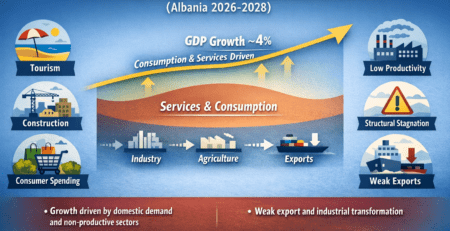

At the beginning of 2026, the euro has fallen to historically low levels against the lek (96.5–96.7 lek), producing a contradictory situation for the Albanian economy, where on the one hand macroeconomic stability and low inflation are presented at the aggregate level, but on the other hand there is strong and persistent pressure on the export sector.

The strengthening of the lek, fueled by tourism, foreign investments and foreign currency inflows from various sources, now entering the fourth year of its aggressive appreciation, has begun to turn into a structural risk for the competitiveness of domestic production.

For exporters, especially in garment manufacturing, agriculture, textiles, footwear and processing industries, the problem is clear, as revenues in euros and costs in lek have created a “squeeze” on profits from previous years, which according to the latest assessments from the sector reaches real losses of 15–25% in some segments.

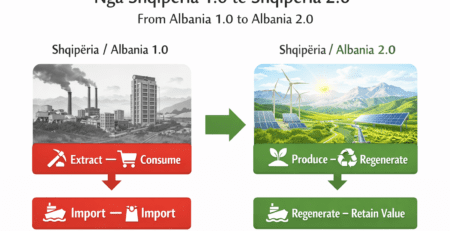

If this dynamic continues without systematic intervention, the risk is not simply cyclical, but silent deindustrialization, as we saw in 2025 with a contraction of exports in lek terms / domestic nominal terms, job losses in some sectors and a shift of capital towards non-productive activities.

However, in 2026 an important paradigm shift is being observed.

Exporters are moving away from the logic of complaints and emergency requests for subsidies, towards a more professional and strategic approach, for a structured dialogue with the government, the Bank of Albania and regulatory institutions, with a focus on medium-term solutions and not on ad-hoc reactions.

This opens the way towards a National Export Strategy (similar to other countries in Europe) [1] in three main directions.

The first pillar, financial and fiscal architecture for resilience to exchange rate risk

The first pillar of a national export strategy should be the construction of a comprehensive financial architecture, which does not aim only to mitigate immediate losses from exchange rate fluctuations, but also strengthens the structural base of the productive sector. Protection from financial risk (financial hedging), often perceived as a technical instrument of banks, should be transformed into a strategic pillar of industrial and trade policy. It should be not only a protection mechanism, but also a tool that increases business credibility, reduces risk and creates space for long-term planning.

In practice, forward contracts with domestic banks enable exporters to fix the exchange rate for payments they will receive after several months. For example, a company expecting 500,000 euros after six months can use hedging to secure a more favorable rate than the one that may depreciate in the future, avoiding losses that otherwise could reach tens of millions of lek. With this mechanism, the strengthening of the lek avoids becoming a structural risk, making the export sector much less vulnerable and less threatened in terms of the sustainability of its finances. However, to make this accessible for SMEs, public guarantees or subsidies for hedging costs are needed, as some Eastern EU countries do.

But the policy of protection from exchange rate risk cannot rely only on hedging.

It must be part of a comprehensive fiscal and supportive package, which not only reduces losses from exchange rate fluctuations, but also encourages investment and increases productivity.

In practice, the government should undertake targeted and direct measures, such as (a) tax relief for those exporters who choose to invest in technology and automation, making companies more competitive and more resilient to exchange rate pressures, (b) favorable loans in lek, with low preferential rates, which reduce the cost of capital and allow firms to make strategic investments without high financial risk, and also (c) subsidies for European certifications and standards, such as ISO or CE, which not only increase the added value of products, but also strengthen the Albanian brand in international markets, making it known for quality and reliability.

Thus, hedging becomes part of an ecosystem supported by fiscal policy, which helps exporters move from a low-cost model towards a strategic model, oriented towards quality, innovation and branding.

In this way, business profits no longer depend only on the exchange rate, but on quality, innovation and strategic positioning in the global market. Strategically, such a financial and fiscal architecture not only protects exporters in the short term, but also creates the basis for a more sustainable and competitive productive sector, capable of facing the challenges of exchange rate fluctuations and integration into European markets.

The second pillar, regulatory policies and competition transforming from passive protection towards active productivity

If protection from exchange rate fluctuations has so far been the main focus of export policies, the European trade reality shows that this is not enough. An export economy cannot remain competitive by relying simply on protective measures, but it needs a strategy that empowers businesses to produce more with less, moving from a passive approach towards active productivity.

This requires well-thought-out and coordinated interventions. First, regulatory costs must be reduced, especially in key sectors such as energy and local tariffs for exporting producers. Energy prices for industrial producers remain a challenge (even though they have fallen from the 2022 peak) and their reduction would have a multiplier effect.

Any reduction of these costs would not be just short-term relief, but the creation of space for investments in technology and automation, increasing efficiency and reducing dependence on external factors such as the exchange rate.

Second, the simplification of administrative procedures is key. Today, high bureaucracy and excessive documentation slow down business and increase transaction costs. By modernizing services, digitalizing permits and certificates, and removing unnecessary barriers, exporters can operate more flexibly, make better use of their resources and focus on product development and market expansion.

Third, exporters should orient their activity towards premium products and building the Albanian brand. Moving from the classic low-cost and subcontracting model towards production with higher added value and European certifications not only increases profits, but enables companies to compete with quality, innovation and integration into more advanced value chains. A firm that offers certified products and an Albanian brand enters market segments that require higher standards, avoiding the pressure of competition from countries with lower costs.

In this way, regulatory policies are transformed from an obstacle into a strategic engine. Reducing costs, simplifying procedures and encouraging premium production build an ecosystem that increases productivity and competitiveness of the export sector. Through it, Albania not only faces the pressure of European markets, but transforms every challenge, including the strengthening of the lek, into an opportunity to increase added value and product diversification.

The third pillar, Integration into the EU – from exchange rate challenge to development catalyst

European integration should not be seen simply as a bureaucratic process or as an additional source of financing. EU funds, such as IPA III and the Growth Plan, offer extraordinary opportunities to rebuild the Albanian export model and to transform exchange rate challenges into a strategic advantage.

Specifically, these funds can be used to build public guarantees for hedging, which cover part of the financial costs for SMEs, enabling them to manage exchange rate risk without being exposed to large losses.

They can create advisory networks and training, with European experts, for risk management and the certifications necessary for international markets. At the same time, the funds can finance investments in technology and innovation, increasing productivity and the competitive capacity of Albanian firms.

In this sense, negotiations with the EU and the opening of economic chapters are not only a formality, because they create the opportunity for a parallel dialogue with European financial institutions, positioning Albania not as a victim of the strengthening or depreciation of the exchange rate, but as an actor that uses integration to strengthen competitiveness and to build a more sustainable export sector.

The depreciation of the euro against the lek is not simply a monetary episode, but a test for the country’s economic model.

If an integrated strategy is built in the three directions (financial and fiscal, regulatory and competitive, as well as integrative with the EU), this crisis can be transformed into a catalyst for a more resilient, more productive and more European economy.

In the end, the exchange rate challenge is not simply a problem for exporters, but a test of maturity for Albanian economic policymaking. Beyond creating a joint calendar of discussion and participation between exporters and Albanian institutions, it is essential to also open a parallel roundtable with EU institutions in Tirana, which would enable better adaptation and protection of the export sector, learning from the experiences of Bulgaria, Poland, Romania and Croatia.

This would position Albania not as a passive party, but as a proactive actor that uses European integration to build modern industrial and trade policies.

As a first concrete step, a National Council for Export Policies (a tripartite institutional platform) government-Bank of Albania-exporters’ representatives should be established within the first 3-6 months of 2026, with a clear mandate to draft a national export strategy. This body should have direct access to European expertise, work within defined deadlines and produce operational, not declarative documents, linking monetary, fiscal, regulatory and integration policies into a single development framework.

In this way, the exchange rate challenge ceases to be a permanent risk and becomes a catalyst for structural reform, where exports no longer depend on the randomness of the exchange rate, but are built on real competition, sustainable productivity and functional integration into the European market.

[1] https://mpo.gov.cz/assets/cz/zahranicni-obchod/podpora-exportu/exportni-strategie/2024/7/Export-Strategy-2023-2033_1.pdf

https://tradepromotioneurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/TPE-Manifesto-2024.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.