How much does administration cost us and how much value does it produce for the economy and society?

In every functional economy, the state is not measured by how many people it employs, but by how much real value it creates for society with the resources it consumes.

In Albania, the public administration has become one of the largest and most persistent expenditures of the budget, while citizens’ assessment of service quality remains low and institutional trust fragile.

This creates a fundamental tension, with a state that costs more and more, but does not produce proportionally more order, efficiency, or development.

The approach to administration can no longer remain moral or political, as it must be economic. What real relationship exists between the cost we pay and the value we get back as a society?

In this sense, the problem is not only how many employees are hired in the state, but how much each of them really costs the public system and what economic weight these expenditures have in an ever-growing budget.

In Albanian public discourse, the cost of a public employee is usually reduced to the monthly salary, as if the state were a small business that only pays wages.

In reality, salary is only the tip of the fiscal iceberg.

The state budget for 2025 itself projected total expenditures of around 831.8 billion lek, while in the 2026 budget this amount increases to 886.7 billion lek, or about 31.9% of GDP. This budget expansion does not simply reflect an increase in investments or services for citizens, but above all an increase in the cost of the state apparatus itself.

From this total amount, 704.7 billion lek in 2026 are current expenditures, meaning expenditures for the daily functioning of the state. Public personnel alone costs around 140 billion lek, or 5% of GDP, where 119.4 billion are wages and 19.2 billion are social insurance contributions. This means that about 1 in every 6 lek of the budget goes directly only to the salaries and insurance of the administration.

But the cost of the state for itself does not stop here.

Operational and maintenance expenditures of the administration reach 84.9 billion lek in 2026 (3.1% of GDP), which include buildings, energy, IT, equipment, rent, and institutional functioning. These are necessary expenditures just to keep the administrative structure alive, regardless of whether it produces real value for society or not.

Another component is the financial cost of the state itself as a debt-based organization. Interest on public debt alone in 2026 reaches 64.2 billion lek, or 2.3% of GDP, money paid not for services, but for the cost of borrowing.

If we sum these three groups, personnel (140 bn), operational expenditures (85 bn), and interest (64 bn), it turns out that around 289 billion lek per year, or over 32% of the entire state budget, go directly to the functioning of the state apparatus itself.

This amount essentially represents the minimum cost that society pays just for the state to exist as an administrative structure, before we even talk about real services, investments, or development policies. In this sense, the state consumes over 1/3 of public resources for itself, while the value it produces for citizens and the economy remains unmeasured and structurally low.

To better understand how this money is spent on administration, we need to look at a detailed calculation of the real cost of a public employee, a calculation that goes beyond the salary he or she takes home.

The average gross salary in the public sector is around 92–100 thousand lek per month, which translates into around 1.1–1.2 million lek per year for each employee. But this amount is not the real cost to the budget, because on top of this are added social and health insurance contributions, which make up about 25–30% of the gross salary, bringing the direct annual cost to around 1.38–1.56 million lek per employee.

Expenditures for salaries and contributions of public employees alone in the 2025 budget reach around 128.7 billion lek, only for base salaries, without calculating the cost of functioning and future obligations.

This is only the first layer of cost.

Every public employee operates within a physical and institutional structure that has unavoidable expenses: offices, buildings, electricity, equipment, IT systems, and maintenance. According to World Bank estimates on public expenditures, these cost on average an additional 20–40% on top of salaries.

In concrete terms, even a conservative estimate of 20–30 thousand lek per month for operational expenditures per employee translates into an annual cost of 240–360 thousand lek.

When internal administrative costs are also added, such as human resources, procurement, and management, which can reach 15–20 thousand lek per month, the total indirect cost goes to around 420–600 thousand lek per year for each individual in the administration, in addition to salary and insurance expenditures.

The third dimension, often ignored in the debate, is the systemic or latent cost, which includes the long-term obligations of the state toward its employees, especially other social benefits and training.

According to IMF fiscal models and the state budget, this latent cost can represent about 20–30% of the annual salary, which for an average employee means an additional around 220–360 thousand lek per year, spread over time, but in reality charged to the system.

When these three layers (direct, indirect, and systemic) are combined, it results that the real cost of a public employee is about 1.7 to 2.5 times higher than the gross salary.

For an average salary of about 95 thousand lek per month (1.14 million lek/year), the total cost for the budget is calculated at around 2.12–2.44 million lek per year per employee, combining direct costs of around 1.42 million lek, indirect costs of around 420–600 thousand lek, and systemic costs of around 280–420 thousand lek.

At the macro level, this translates into a fiscal burden of around 296–341 billion lek per year just to keep the public administration functional, an amount that comes directly from the budget and is paid by the taxes paid by citizens and businesses.

When compared with total expenditures of the 2026 budget of around 886.7 billion lek, where a large part goes to maintaining the state apparatus, it becomes clear that this expenditure structure is not simply an administrative issue, but a macroeconomic problem with a direct impact on fiscal sustainability and the efficiency of public services.

The real value of public service and the invisible balance of efficiency

In economics, efficiency is measured as the ratio between added value and total cost.

In the private sector, this ratio is strict and direct. An employee must generate at least 2–3 times his salary just to cover costs, while in high-value sectors, such as IT or professional services, the ratio reaches 4–6 times, otherwise economic activity becomes unsustainable.

In the Albanian public sector, this principle is not really applied, because performance is assessed mainly on the basis of formal inputs (number of files, working hours, procedures fulfilled), as also reflected in the reports of the State Supreme Audit Institution (KLSH) and in the practices of the Department of Public Administration (DAP).

Real output, meaning the concrete value created for citizens and the economy, remains almost unmeasured. Official publications do not contain performance indexes that measure time savings for citizens, cost reductions for businesses, improvement in service quality, or the economic impact of administrative interventions.

In the vast majority of central and local administration, especially in municipalities and regulatory institutions, real productivity remains very low or negative, due to delays, overlapping competencies, and corruption. When the efficiency ratio falls below 1, meaning when the cost of a position is greater than the value it creates, the administration ceases to be a service instrument and turns into a net burden for the economy.

From available analyses and reports summarized by KLSH and the Ministry of Finance, the average efficiency ratio in central and local administration in Albania is estimated to be around 0.4–0.6, meaning that for every 1 lek spent, the administration produces only 40–60% of the real value that could be generated. Compared with the Western Balkans, where the efficiency ratio is estimated around 0.7–0.8, and with the EU, where it often exceeds 1.2–1.5 thanks to advanced performance measurement and functional digitalization, Albania appears far behind in real benefit from every budget unit, highlighting the urgent need for structural reforms and clear output measurement.

Albania compared with the Region and the EU and the paradox of public efficiency

Albania spends relatively little on public administration, around 4.5–5% of GDP on wages, compared with 8–10% in EU countries, but productivity remains low, highlighting a structural problem and not merely a fiscal one.

In the Western Balkans, the average public gross salary is around 900 euros, compared with around 1,000 euros in Albania (around 100,000 lek/month in 2025), but the main challenges are similar, with politicization of the administration and lack of real performance measurement.

In the EU, the total cost of public administration is much higher, around 7,142 PPS per capita in 2021, with a tendency to increase to 8,000–9,000 PPS in some countries in 2025, but service output is proportional and often above standards, due to advanced performance measurement and functional digitalization.

Albania shows a paradox, as it has low cost, but value is even lower, where billions of lek are spent on the administrative structure without generating real effects for citizens and the economy.

For example, GDP per capita in PPS for Albania in 2025 is around 43–47% of the EU average (around 23,000–24,000 USD PPP vs. 50,000–66,000 USD PPP in the EU), confirming the large convergence gap.

This comparison shows that the problem is not only how much we spend, but how the public apparatus is built and how much value it produces for society, highlighting the need for structural reforms and clear efficiency measurement.

Thus, if we address the cost problem, it is evident that the e-Albania platform today offers around 95% of public services online, reducing physical contact and some operational costs, such as documentation expenses and citizens’ time at counters.

However, without real simplification of administrative procedures and without performance measurement, this does not increase the productivity of the administration, and many bureaucratic barriers remain.

While in the EU digitalization has brought cost reductions of 18–34% and an increase in public output, in Albania and the region it often turns only into digital bureaucracy, where complex processes remain untouched.

The result is that even though there have been limited cost reductions, the gap between expenditures and the real value that citizens receive remains large, leaving the administration to produce less than it costs.

Corruption and trust as economic blockers

In Albania, the level of trust in public institutions remains low, as evidenced also by EU Progress Reports.

Corruption and clientelism increase costs for citizens through bribes, delays, and prolonged procedures, creating a net negative cost. For every lek spent in administration, the real value produced is often lower, hindering economic development.

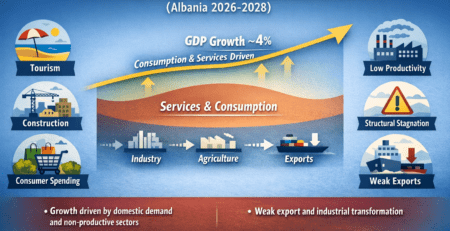

The forecast for 2026+ remains worrying.

If public structures continue to function according to the same practices, every new investment in administration will only increase the fiscal burden, without improving citizens’ lives and deepening the gap between expenditures and real value.

This is the theoretical axis of the entire argument.

Where the efficiency ratio is below 1, the state does not produce value, but consumes development, sealing the status of the administration as a structure that relies on the economy and not vice versa.

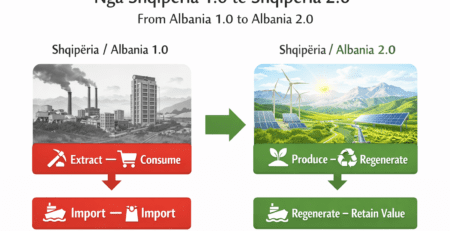

The solution is not found simply in the form of contracts or wage structures, but in real reform, oriented toward clear performance measurement with accurate KPIs, meritocracy, and deep digitalization, as it functions in the EU.

The lack of will for deep reform will preserve an administration that consumes public resources, while the small and fragile economy will continue to keep the state alive, turning every cosmetic attempt at reform into a false illusion of progress.

Notice!

Reports that have been published mainly by international organizations (World Bank, OECD-Sigma, EC, UNDP), as well as academic studies. They use indicators such as reduced procedure time, fiscal savings, citizen satisfaction, and impact on GDP. The e-Albania platform is often cited as an example of time savings (over 95% services online, reducing physical visits).

Many indicators are perceptual or general, not always standardized quantitative KPIs by DAP or the Albanian government. Measurement of economic impact is often based on estimates, not real-time data. More detailed measurements are found in reports on institutional performance by KLSH or SIGMA for monitoring PAR (Public Administration Reform) reforms, but they still do not reflect the real administrative output, as expr.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.